Trees Not to Plant

To Plant or Not to Plant: Trees to Avoid Planting in Your Yard

These endangered trees are likely to decline or die from the impacts of non-native insects and pathogens.

By: Alison Hitchcock, Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener

Master gardeners are often asked for recommendations of trees to plant. These requests come in two flavors: what is the best tree for the clients’ preferences and landscape conditions, or what trees are inappropriate and best avoided? Many reputable websites provide numbered lists of the “best backyard trees” or, conversely, a catalog of “trees that you should, never, ever plant.”

The compilations of “trees that you should never, ever plant” tend to concentrate on undesirable characteristics such as messy or foul-smelling fruits, brittle stems, or heavy pollen production. Few include warnings concerning those species likely to decline or die from the impacts of non-native insects and pathogens.

The purpose here is to highlight tree species especially vulnerable to current and looming threats and suggest they should be added to your own “avoid planting” list. Property owners are encouraged to take early action by identifying unhealthy trees on their property during National Tree Check Month.

Most of the public has some awareness of invasive pests; gypsy moth, chestnut blight, and Dutch elm disease are well-known examples. Data from our plant clinics shows that many other pests, more recent or less widespread, are well established in our area and have the potential for severe impacts of which the local community is generally unaware. The local community is generally unaware of many of these.

| Trees Vulnerable | Agent | Comment |

|

True firs: Noble, Fraser, Pacific silver |

Balsam woolly adelgid (Adelges piceae) | Most commonly seen in MG plant clinics on Noble and Pacific silver trees. Grand fir was heavily affected in Oregon but not as severely here. |

| Native white pines (5 needles) |

White pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola) |

2 and 3 needle pines were not affected. Non-native 5-needle pines have much lower rates of infection than native pines. |

|

Birch (selected species) |

Bronze birch borer (Agrilus anxious) |

Native pests affecting non-native birches |

| Ash |

Emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) |

Not yet a problem, but it is coming soon |

| Beech |

Beech bark scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga) Beech leaf disease (unknown cause) |

Not yet a problem, but it is likely to be soon |

Chronic infections of balsam woolly adelgid result in gouting of the bark.

© Photographer: W. M. Ciesla, Forest Health Man. Intl, Bugwood

Balsam Woolly Adelgid

The balsam woolly adelgid (BWA) (Adelges pinceae) is a widely established non-native insect that has become a pest of significant importance to all true firs around the county. The adelgid originated in Europe and first appeared in the Northwest during the 1920s. BWA shows up at the clinic every year, primarily on noble fir trees.

Adelgids are small, aphid-like insects that are always associated with conifers. A white and dense woolly wax covers adult adelgids. As it sucks sap from branches and boles (main stem below the branches) of a host tree, the balsam woolly adelgid injects a salivary substance that induces changes to the sapwood. The tree responds with knoblike, “gouty” swellings, which reduces the tree’s ability to translocate food and water.

Trees with crown infestations of BWA may take many years to die, while those with severe stem infestations die within five years, which is particularly important to Christmas tree growers. Control is difficult without a strict regimen of insecticide applications. Noble fir trees with chronic infections are scattered throughout Skagit County. (This author has yet to see a mature tree free of the disease). Look for tall trees with thinning crowns, dead branches, and an unaesthetic appearance.

White pine blister rust on a twig. © Photographer: USFS Region 2 Bugwood

White Pine Blister Rust

White pine blister rust is a fungal pathogen introduced from Asia. The fungus only attacks pines with clusters of 5 needles (white pines and not those with 2 or 3 needles.) This disease has virtually eliminated western white pine in western forests, causing a severe decline in native whitebark and bristlecone pines, both important ecological species. While all North American white pines are highly susceptible, non-native 5-needle pines have much lower infection rates.

The disease entered the US through infected nursery stock from Europe during the 1900s. Because tree nurseries in the United States were not yet well established, seedlings were grown (using native eastern white pine seed) in Europe and shipped to this country to meet reforestation needs. Because the first signs of infection are very subtle, the rust-infected seedlings were unknowingly imported.

White pine blister rust affects trees of all ages and sizes but spreads more quickly in areas with extended, cool, moist conditions during late summer and early fall. Pines are infected through needle stomata on wet needles. Following infection, the fungus grows down the needle and into the bark, where a perennial canker forms, eventually girdling and killing the branch. Branch infections are not too serious unless very abundant; stem infections are generally fatal.

Most infections occur near the ground, where needles remain wet from dew and poor air circulation. Infections are apt to be lethal in young trees because branches are near ground level, and cankers develop closer to the main stem. Early pruning of diseased branches can be effective in reducing infection movement into the main stem and also help to increase air exchange. Prune juvenile trees as early as possible without removing excessive crown area, and gradually remove lower branches as the trees mature.

Those familiar with the Salal Native Plant Garden located south of the Discovery Garden (on Memorial Highway) may remember a western white pine that once existed immediately behind the Discovery Garden greenhouse. Despite heroic pruning efforts to keep the infection from spreading, the tree slowly succumbed to the disease and died. A small shrub in the Discovery Garden’s Fall and Winter garden room recently suffered a similar fate once the disease entered the main bole.

The current strategy for reintroducing western white pine to state and national forests is to increase the frequency of rust-resistant individuals across the landscape. The USDA Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Region has had a screening and breeding program to develop resistance to the disease since the late 1950’s. Each year, resistant stock is grown at government nurseries to be out-planted in Oregon and Washington forests; unfortunately, infection rates continue to be high.

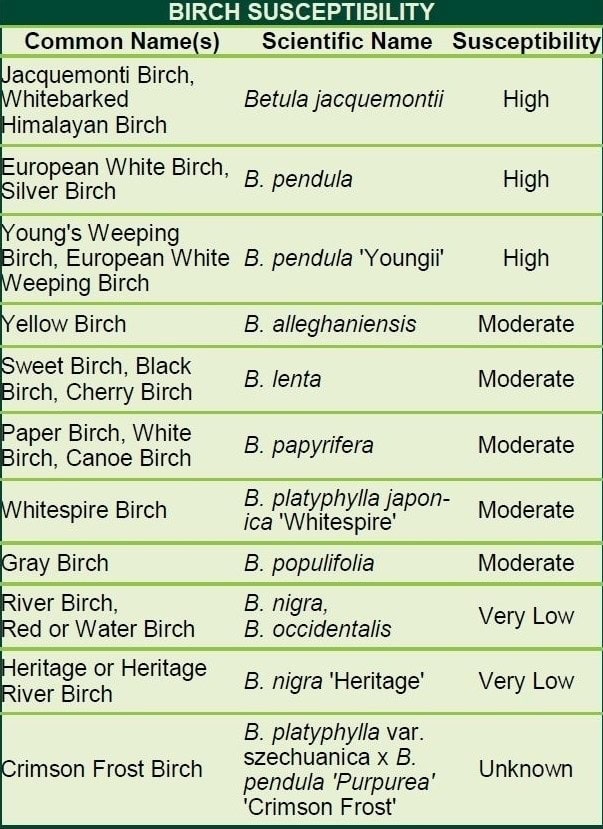

Bronze birch borer chart. © Oregon Department of Forestry

Bronze Birch Borer

The bronze birch borer is a native insect that is a serious pest of ornamental birch trees, especially some white-barked species. While all species of birch can be attacked, non-native species are the most susceptible to injury. Borers primarily attack weakened, older, or drought-stressed trees. Problems regarding declining and dying birches have become an increasingly common issue seen at plant clinics during the last five years due to recurring droughts.

An early warning sign of borer damage is yellowing and thinning of foliage in the upper tree crown. The foliage will turn brown and drop from the branches by late summer. Infestations usually begin in ¾” to 1” diameter branches, with symptoms progressing down the tree to the main trunk over successive years. Borers mine flat, irregular, winding galleries just beneath the bark, feeding in the phloem and severely injuring the vascular system. Attacked trees that survive will form callous tissue in the mines, which will become raised areas visible through the bark. Adult emergence holes are ‘D’ shaped and commonly accompanied by mottled, brown staining on the bole.

Borers do not survive in healthy trees, so keeping trees vigorous and adequately watered and planting resistant varieties is advised. A good look at the effects of borer damage can be seen on the non-native birches planted throughout the Fred Meyer parking lot in Burlington.

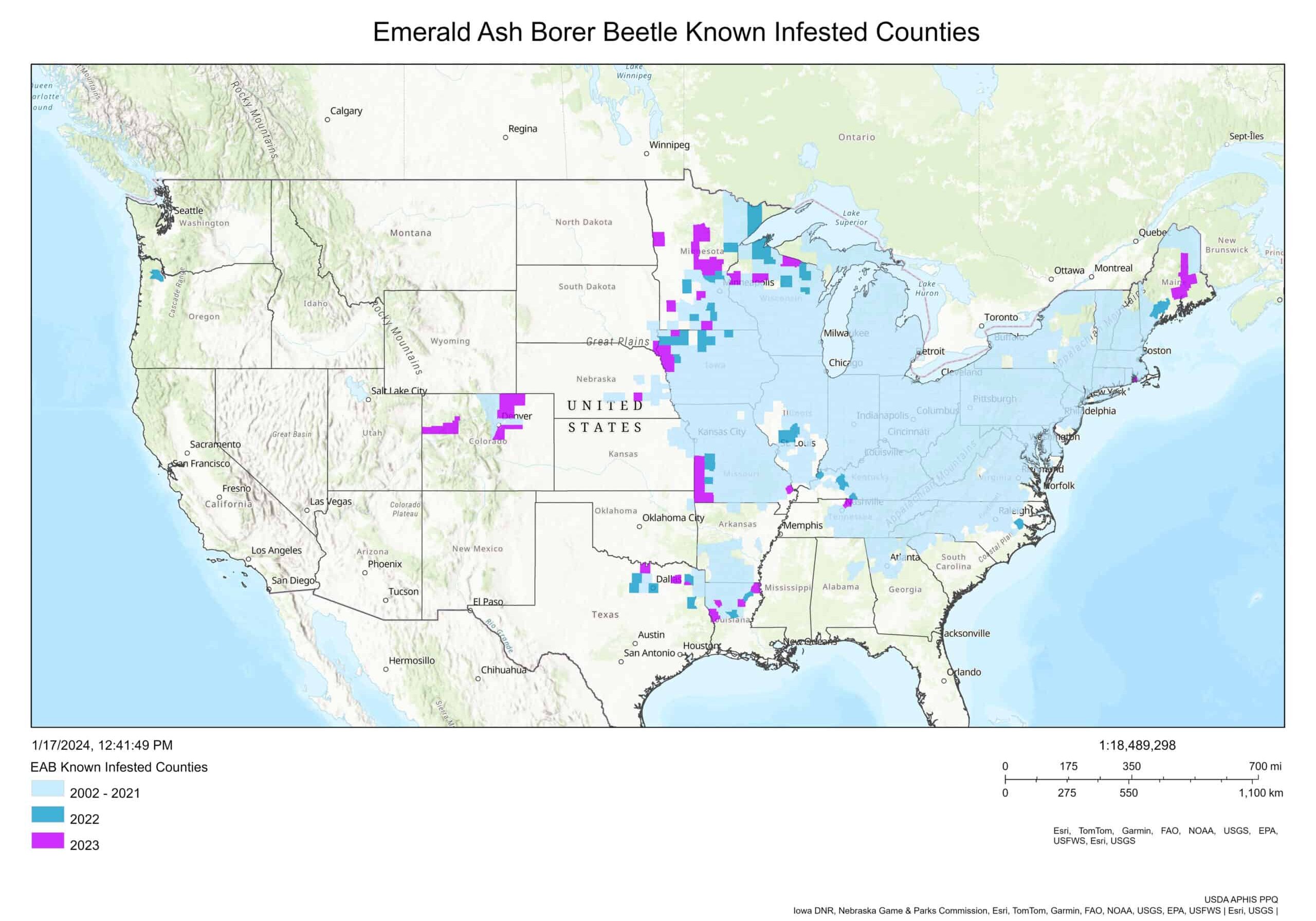

Emerald Ash Borer

The emerald ash borer (EAB) is a bright, green, buprestid beetle that lays eggs in the bark of ash trees. The larvae bore into the tree and feed on phloem tissue, effectively gridling the tree and resulting in tree mortality in as little as two years.

Research has shown that EAB infested ash trees in Michigan 10 to 12 years before its initial discovery in 2002. The EAB probably entered the United States on solid wood packing material carried in cargo ships or planes originating in its native Asia. Since its arrival, the EAB has spread rapidly across North America and wiped out ash tree populations in the northeast. Green, white, black, blue, and pumpkin ash are on the listed “critically endangered” list. The insect has been found in 35 states and at least 5 Canadian provinces; it was discovered in Forest Grove, Oregon, in June 2023. Read more about the emerald ash borer in the WSU Publication Emerald Ash Borer and Its Implications for Washington State:https://pubs.extension.wsu.edu/Product/ProductDetails?productId=4755

Research trials have shown that Oregon ash (Fraxinus latifolia), our lone native ash, is highly susceptible to EAB. Ashes have not been widely planted in our residential landscapes but are common in nearby shopping centers and other public areas. Ashes can be found in Burlington’s Best Buy, Costco, and Cascade Mall parking lots.

Beech Bark and Beech Leaf Diseases

Beech bark disease (BBD) is a disease of American beech, resulting from the infestation and feeding by the beech bark scale followed by infection with several native fungal species. The fungi cause bark lesions that grow and eventually girdle the tree. Beech scale was introduced into Nova Scotia from Europe in the 1890s and has been slowly progressing through the range of American beech as far south as Tennessee and west to Wisconsin. Over 50% of infected beech trees die within ten years of infestation.

Beech leaf disease (BLD) has been discovered recently, and much about it, including the full cause and how it spreads, is still unknown. It appears to be associated with a nematode, Litylenchus crenatae mccannii. First spotted in the northeast, the disease causes parts of leaves to turn leathery and branches to wither. The blight can kill a mature tree within six to ten years. It has now been documented in Canada and eight other US states.

Timely Detection Increases the Chance of Successful Pest Management Efforts

We have yet to see either disease in Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener Plant Clinics since beech trees are not native to the Northwest, nor are they widely planted in our area. As a precaution, we do not recommend planting beech.

Every August, the Washington Invasive Species Council asks residents to check the trees on their property for signs of harmful insects or unhealthy trees as part of the National Tree Check Month. As summer progresses, many of the visible impacts from invasive species are most visible. Residents who suspect they have spotted an invasive species or tree disease should submit a report with detailed photographs to the Invasive Species Council’s mobile app or web portal https://invasivespecies.wa.gov/report-a-sighting/.

Pest infestations can be managed or even eradicated if caught early enough. Timely detection increases the chances of success and minimizes the cost of pest management efforts. A few minutes of inspecting your trees this August will help spot invasive insects, plant pathogens, and other types of damage before they have a chance to take hold.

Alison Hitchcock

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Alison Hitchcock has been a Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener since 2001. Prior to retirement, Alison worked for the Department of Natural Resources as the Northwest Regional Silviculturist.

Join us this coming Tuesday for a free Know and Grow Lecture—

Know & Grow Lecture Series

Season Extenders

Presented by Hallie Kintner

Tuesday, August 20, 2024 ~ 1 p.m.

Free Admission

NWREC Sakuma Auditorium

16650 State Route 536, Mount Vernon

REFERENCES AND RESOURCES:

Burns, K.S., Schoettle, A.W., Jacobi, W.R., Mahalovich, M.F. (2008) Options for the management of white pine blister rust in the Rocky Mountain Region. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-206. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 26 p.

Cale, J.A., Garrison-Johnston, M.T., Teale, S.A. and Castello, J.D. (2017) Beech bark disease in North America: Over a century of research revisited. Forest Ecology Management: Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Netherlands pp 394:86–103.

Davis, C. and Meyer, T. (2004) Field Guide to Tree Diseases of Ontario. Northern Ontario Development Agreement’s Northern Forestry Program Report TR-46: Sault St. Marie, Ontario, Canada.

Flower, C.E., Knight, K.S., and Gonzalez-Meler, M.A. (2013) Impacts of the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) induced ash (Fraxinus spp.) mortality on forest carbon cycling and successional dynamics in the eastern United States. Biological Invasions. 15(4): 931-944.

Lovett, G., et al. (2016) Nonnative forest insects and pathogens in the United States: Impacts and policy options Ecological Applications: Washington D.C. vol. 26 (5), pp 1437-1455.

Goheen, E.M., Willhite, E.A. (2006) Field Guide to the Common Diseases and Insect Pests of Oregon and Washington Conifers.USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region. R6-NR-FID-PR-01-06. Portland, OR.

Johnson, W.T., Lyon, H.H. (1988) Insects that Feed on Trees and Shrubs. Cornell University Press: Ithaca, New York.

Scharpf, R.F. (1993) Diseases of Pacific Coast Conifers. USDA Agriculture Handbook 521: Albany, CA.

Shaw, D.C., Oester, P.T., Filip, G.M. (2009) Managing Insects and Diseases of Oregon Conifers. Oregon State University Extension Service EM 8980: Corvallis, OR.

Sinclair, W.A., Lyon, H.H., Johnson, W.T. (1987) Diseases of Trees and Shrubs. Cornell University Press: Ithaca, New York.

A Second Act for Your Square 1-Gallon Pots at the Discovery Garden!

Bring your leftover square 1-gallon pots to the Discovery Garden (16650 State Route 536, Mount Vernon). The bin for recycling the square 1-gal pots is located in the parking lot, just north (to the right) of the main entrance.

We only need square 1-gallon pots like the ones pictured below (bottom right). The recycling bin will be available now through fall. Simply put your pots into the bin, and we take care of the rest!

This is excellent advice. Thanks Alison!

Agree, very good article!