Hypertufa Containers

Hypertufa Troughs Serve as Lowland Homes for Native Alpine Plants

Grow these tiny gems seen on an alpine hike

By: Sonja Nelson, Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener

Nestled low to the ground among the peaks of the North Cascade Mountains are tiny alpine plants that delight hikers as they stroll the high country of Skagit and Whatcom Counties. If these hikers are also gardeners, it is tempting to dig a few of these gems to take home and plant in their home garden. Digging and removing plants is, of course, prohibited on public lands, including national parks, forests, and recreational areas. Moreover, the plants most likely would die when snatched out of their high-altitude environment and planted in the soils found in the lowlands of our ecoregion.

However, alpine gardening enthusiasts have found a solution to recreate the beauty they see in the alpine regions of the North Cascades. Using containers created to grow plants away from their native environment and plants purchased from nurseries specializing in alpine plants, gardeners can successfully grow these tiny gems seen on an alpine hike.

The containers, called "hypertufa troughs," are constructed to provide the specific requirements alpine plants and succulents need to thrive. They also blend nicely into a garden or can be placed on a deck or patio.

Hypertufa troughs originated from the naturally occurring tufa rock, a type of limestone formed when carbonate minerals precipitate out of water and build up around organic matter, eventually decomposing, leaving a porous rock. English farmers of the 1800s chiseled feeding troughs for their animals out of this rock. Years later, creative gardeners adopted these old containers, covered in moss and worn by decades of exposure to the elements, as decorative planters. A few of these sought-after antique troughs are still found in Europe but are often too heavy and expensive to transport across the Atlantic. (1)

Since tufa rock was not readily found and available in the US, gardeners in the 1930s—1940s began to make tufa-like troughs using a mix of ingredients with Portland cement. They called them "hypertufa.” (2)

Growing small alpine plants in hypertufa troughs has many advantages. The trough materials serve as insulation against extreme hot and cold temperatures that can occur in our ecoregion. The troughs also drain well, so standing water is never a problem, and the roots of alpine plants grow into the porous hypertufa and tend to thrive.

In addition, the Portland cement in the hypertufa mix slowly releases some calcium and magnesium that plants need. And, because the trough is relatively lightweight, they can be moved from place to place in the garden for the best exposure through the seasons. (2)

Ecoregions

Growing alpine plants in hypertufa troughs gives gardeners the pleasure of seeing them close to home in their gardens and protects them from the possible ravages of warm summers in their native locations.

Skagit Valley is located in the Puget Trough ecoregion, with mild, wet winters, and warm, dry summers. Here, precipitation averages 40 inches per year, with a mean January temperature of 39° F and a mean July temperature of 65°F. This climate differs from the climate of the North Cascades ecoregion, where many of our Washington native alpines for our hypertufa troughs grow in the wild. High elevations in the alpine regions are often covered with snow for many months. (3) The North Cascades Highway (State Route 20) traverses this ecoregion's subalpine and alpine sections.

The Plants

The choice of North Cascade alpine plants for troughs is considerable. To get started, as an example among alpine plants, choose from the mountain heathers, the saxifrages, and the gentians.

White mountain heather (Cassiope mertensia) near Mt. Shuksan in the North Cascades. © Sonja Nelson

Mountain Heathers

The common name "heather" can refer to many different highland species throughout the world. North Cascade heathers are called "mountain heathers" and include the genera Cassiope and Phyllodoce. Common names include white mountain heather, Alaskan mountain heather, pink mountain heather, and yellow mountain heather. (6)

Saxifrages

Members of the genus Saxifraga are widespread in the North Cascades, many of which grow in the subalpine and alpine regions. Examples seen by the author are Tolmie's saxifrage (Saxifraga tolmiei) at Chain Lakes, Alaska saxifrage (Saxifraga ferruginea) at Twin Lakes, and western saxifrage (Saxifraga occidentale) on Chowder Ridge (Pojar and Mackinnon1994).

Saxifrage at Bagley Lakes in the North Cascades. © Sonja Nelson

Broad-petalled gentian (Gentiana platypetala) at Cutthroat Pass in the North Cascades. © Sonja Nelson

Gentians

Members of the genus Gentiana are also widespread in the North Cascades. Four gentian species are native to the North Cascades: king gentian (Gentiana septum), broad-petalled gentian (Gentiana platypetala), swamp gentian (Gentiana douglasiana), and alpine bog swertia (Swertia perennis). (6)

Although hypertufa troughs are highly suitable for growing alpines at low elevations, many small native plants and succulents also find the troughs an amenable environment for growth and a refuge from fluctuating temperatures.

Growing Mix

The soil mix used in the troughs cannot be the same as the soil in your garden. Alpines especially need good drainage, which means water seeps through the medium quickly and does not pool around the plant crowns.

A basic trough medium recipe is 2/3 to 3/4 by volume potting mix with either peat or coconut coir and 1/3 to 1/4 by volume coarse perlite. Add fertilizer if the soil mix does not include it. (2)

Making Hypertufa

Recipe mixes for hypertufa can be found on the Internet. The recipe below is from Rosemary Read, Editor of The Social Gardener for the Whatcom Horticultural Society.

Lightweight Frost-proof Troughs "Tufa"

by Rosemary Read, Editor, The Social Gardener

Materials Needed (parts by bulk):

- 1 part Portland cement

- 1 ½ parts fine peat (screened)

- 1 ½ parts horticultural vermiculite and/or perlite

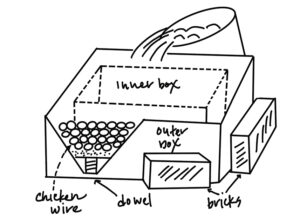

- 2 cardboard boxes (which, when fitted one inside the other, leave a gap of approx. 2 in. between the sides.)

- 2-3 wood dowels (approx. 2 in. long)

- Chicken wire (or metal strips) for reinforcement

Peat Moss and Sustainability

Increasingly, master gardeners are looking towards sustainable materials and encouraging gardeners to use a peat moss substitute whenever possible. Coconut coir is a sustainable product, and can be used instead of peat moss at a ratio 1.5:1 of the coconut coir and cement to water and perlite. However, it does not decompose as quickly as peat moss, which leaves pits and crevices and resembles true tufa rock. The full recipe and directions for using a peat substitute can be found here >

Download the full report debunking the myth of the sustainability of peat bogs by Linda Chalker-Scott, PhD., WSU Extension Urban Horticulturist and Associate Professor.

Download here>

Steps to Making a Hypertufa Pot

Mix the dry ingredients and add water to make a thick, creamy consistency that can be poured. Mix in an old wheelbarrow, bucket, or container that can be moved and washed out when the project is complete.

1) Set up the outer mold cardboard box where you can move around it freely and where it may be left to harden. It is best to cover surfaces with plastic.

2) Pour mixture into the floor of the outer mold (2" or more).

3) Press the wooden dowels into the mixture. In addition to making drainage holes, the dowels will support the inner box.

4) Place the inner mold on top of the dowel plugs.

5) Place in chicken wire (along sides and corners).

6) Pour in the mixture until it reaches the top.

7) Leave 24 hours. Remove the outer mold (peel off).

8) Rough sides to make it look "old" (chisel).

9) Leave the inner mold longer to harden.

10) Leave trough a week or more to harden before knocking out the plugs.

11) Leave the trough for 2 weeks to "cure" by soaking it in water, which is changed every 2-3 days.

_______ - _______

Safety Warning: Concrete contains chemicals that can cause skin irritation and lung damage. Read the warning labels on the material purchased. When working with concrete, always wear gloves, a facemask, safety glasses, and old clothing. Set up your work area outside, away from breezes, children, and pets.

_______ - _______

Outer box: 16 ½” x 13 ¼” x 8”

Inner box: 13“ x 9 ¼” x 6-8”\

Trough Size (inside): 13” x 9 ¼” x 5 ½”

REFERENCES AND RESOURCES:

1. Carpenter, J. How to Make a Hypertufa Garden Trough. Retrieved from: This Old House.com

2. Chips, L. (2018). Hypertufa Containers. Portland, OR, Timber Press

3. Ecoregions in Washington, Landscape America, (http://www.landscope.org/washington/natural_geography/ecoregions/).Read, R., Personal Communication, (May, 2024). Lightweight Frost-proof Troughs “Tufa” The Social Gardener, Whatcom Horticultural Society, Bellingham, Washington.

4. Reed, W. High and Dry for a NW Icon. (2023, Fall). Washington State Magazine

Retrieved from: https://magazine.wsu.edu/2023/07/31/high-and-dry-for-a-nw-icon/

5. Pojar, J., MacKinnon, A. (1994). Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia and Alaska. Tukwilla, WA, Lone Pine Publishing.

Sonja Nelson

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sonja Nelson is a Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener, Class of 2009.

Questions about home gardening or becoming a master gardener may be directed to: Skagit County WSU Extension Office, 11768 Westar Lane, Suite A, Burlington, WA 98233; by phone: 360-428-4270; or via the website: www.skagit.wsu.edu/mg

Know & Grow

Gardening for Fragrance

Presented by Diana Wisen

Free

Tuesday, June 18 ~ 1 p.m.

NWREC Sakuma Auditorium

16650 State Route 536, Mount Vernon

Visit the annual Open House at the Display Gardens:

Saturday, June 29

10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

Free Admission & Parking

Discovery Garden

16650 State Route 536, Mount Vernon

Learn More >

A Second Act for Your Square 1-Gallon Pots at the Discovery Garden!

Bring your leftover square 1-gallon pots to the Discovery Garden (16650 State Route 536, Mount Vernon). The bin for recycling the square 1-gal pots is located in the parking lot, just north (to the right) of the main entrance.

We only need square 1-gallon pots like the ones pictured below (bottom right). The recycling bin will be available now through fall. Simply put your pots into the bin, and we take care of the rest!