Warmer Summers Impact Local Rhododendrons

From sun scorch to lace bug, local gardeners protect their beloved rhododendrons with these conscientious tips.

Subscribe to the Blog >By Sonja Nelson, Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener

Author Sonja Nelson

Rhododendrons in our gardens, along with the native state flower Rhododendron macrophyllum, the Western or Pacific rhododendron in our woodlands, are facing the vagaries of climate change here in the Pacific Northwest as well as worldwide. Gardeners in our moderate climate can no longer assume our benevolent climate will continue its unstinting support for the genus Rhododendron. According to the World Meteorological Organization, the average global temperature in 2024 was the warmest year on record at about 2.7° F or 1.55° C above preindustrial levels. Higher temperatures do not bode well for rhododendrons. They like moderation!

Rhododendrons have a long history in the Pacific Northwest. Native Americans used the flowers of rhododendrons in their dance rituals long before western plant hunter Archibald Menzies identified the R. macrophyllum. Menzies was the surgeon-botanist for Captain George Vancouver on board the British ship ‘Discovery’ in 1792. The R. macrophyllum, or Western rhododendron, was sent to King George III and introduced to the Kew Gardens in London. The discovery brought together the British and American plant people who eventually produced a creative milieus communities of rhododendron enthusiasts that made the rhododendron the “King of Shrubs” on both sides of the Atlantic.

References to the Western rhododendron (Rhododendron macrophyllum) date back to native Americans using rhododendron flowers in their dance rituals long before the late 1700s. © Photo: Sonja Nelson

One hundred years after Menzies documented finding the Western rhododendron, the state of Washington sought a representative flower to display in the 1893 Chicago World Fair exhibit. The Washington State Fair Commission asked the state’s women to decide. A letter-writing campaign began, pitting the native rhododendron against, among others, the clover. (The vote was Western rhododendron 7,704 and clover 5,729.) It was officially designated the Washington State flower in 1959.

However, between the time the Western rhododendron was presented at the Chicago World Fair, rhododendron species from Asia, particularly the Himalayas, had been discovered by dedicated British plant hunters and sent back to Britain to adorn gardens there with their vibrant colors and to hybridize. Many Asian species and hybrids were also brought to America, where nurseries introduced them to the Pacific Northwest. Gardeners welcomed them with enthusiasm and love. And the rhodies loved them back with their stunning performance!

Meanwhile, Washington state’s native Western rhododendron grew in its native woodlands as the quietly attractive relative of the more flamboyant Himalayan species. In the 1970s the Western rhododendrons regained popularity as gardening with native plants became popular with the backing of WSU Extension and the Washington Native Plant Society. In 1979, the First World Climate Conference declared climate change a global issue, and rhododendron gardeners’ concern turned to the native Western rhododendron and its environment, along with concern for their rhododendron species and hybrids from afar. The natural environment of the Pacific Northwest, so well suited for much of the genus Rhododendron, was becoming jeopardized by temperature increases and other disturbances to its blissful climate.

The Western or Pacific rhododendron is native to the woodlands of the Pacific Northwest. Image © Oregon State University

One of the most sun-hardy of all rhododendrons, the Jean Marie Rhododendron is noted for its large trusses of deep red, trumpet shaped flowers. © WSU Clark County

The complexity of a warming climate makes it difficult to predict precisely how rhododendrons will be impacted by our specific climate and what to do if it does. For instance, if temperatures increased enough to leave visible sun spots on the leaves of rhododendrons, the rhododendrons could simply be moved to a site with partial shade. However, the effect of a warming climate on plants is not always straightforward.

One solution to protect rhododendron gardens from climate change damage is to find varieties-both species and hybrids-that are tolerant of temperature increase and ensuing weather extremes.

A member of the American Rhododendron Society, C.J. Patterson of Massachusetts, has focused his interest in rhododendrons on finding drought-tolerant rhododendrons for East Coast gardens. He writes that “rhododendrons, in general, are mostly very resistant to dry conditions once they are established,” citing R. carolinianum, R. maximum, and R. catawbiense as drought tolerant. He says one of the most drought-tolerant rhododendron hybrids is the hybrid ‘PJM’ (R. minus var. Carolinian Group x R. dauricum) and other hybrids of the same cross.

The director of the German Rhododendron Society, Hartwig Schepker, supports the idea that the genus Rhododendron is diverse enough to cope with the challenges posed by extreme climate conditions, saying we find them or create new hybrids that will be up to the job.

Another rhododendron expert is Glen Jamieson, the editor of the Journal American Rhododendron Society, who often writes about the impact of climate change on rhododendrons, which, he says, has been relatively minor annually. In coming publications, he plans to summarize the weather impacts on his garden in British Columbia over the past 40 years, where there have been extreme cold, heat, precipitation, and wind events-all of which can be attributed to a changing climate.

Since it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict precisely the effects of climate change on rhododendrons in the future, conscientious basic care is the best way to help them survive hard times in the future. Washington State University lists watering, fertilizing, and mulching as basic care.

Basic Care for Rhododendrons

Washington State University Extension recommends this regimen of basic care:

Watering

- Water rhododendrons at least once a week, or when the top inch of soil feels dry.

- Avoid waterlogged soil, which can damage rhododendrons.

- Water well in the fall to prepare for winter

Fertilizing

- Use a fertilizer made for acid-loving plants.

- Fertilize in the spring when buds swell and in the fall after flowering.

- Follow the product label recommendations.

Mulching

- Use coarse organic mulch, like wood chips, to cover the root zone.

- Keep mulch at least 4 inches deep, but don’t let it touch the base of the plant.

- Mulch helps conserve water, reduce weeds, and moderate soil temperatures

Other Tips

- Plant rhododendrons in well-drained acidic soil

- Avoid dense or compacted soil

- Provide shade or semi-shade

- Prune out dead flowers

- Avoid overhead watering

- Maintain good air circulation

- Prevent injury to reduce the chance of infection

- Clean up and destroy fallen leaves

A Unique Opportunity to Observe Local Climate Change Impact

The coordinators of the various gardens within the WSU Extension Master Gardener Discovery Garden west of Mount Vernon were questioned about possible damage in their gardens due to recent summers with high temperatures. Five coordinators reported no change, and four coordinators reported slight changes. Ironically, six coordinators reported damage from unusual cold spells. The Rhododendron Garden coordinator, however, reported extensive damage to a large planting of small-leaved rhododendrons due to warming temperatures.

Lace bug symptoms on rhododendron leaves © WSU Hortsense Photo by: C.R. Foss

Photo © Sonja Nelson

Rhododendrons are divided into two natural divisions: the lepidotes and the elepidotes. Small-leaved rhododendrons belong to the lepidote division based on the tiny scales on the undersides of their leaves. Elepidotes do not have scales and tend to be large-leaved.

Sun scorch on the leaves of rhododendrons has long been an occasional problem for gardeners, but the warming caused by climate change has introduced a new, insidious avenue for damage–the rhododendron lace bug (Stephanitis rhododendri). Believed to have migrated from California, lace bugs have taken advantage of the longer growing season in the Pacific Northwest and can complete their life cycle, where, in 2023, in the Rhododendron Garden, it laid eggs and, as a result, destroyed a planting of rhododendrons.

Rhododendron lace bug (Stephanitis rhododendri Horvath) © Insect Images Photographers: Seastone, L. and B. Parks

Azalea lace bug (Stephanitis pyrioides) © Photo: Jim Baker, North Carolina State University, Bugwood.org

The lace bug affected rhododendrons with small leaves, mainly in the island meadow section of the Rhododendron Garden, namely hybrids ‘Ramapo,’ ‘Ginny Gee,’ and ‘Patty Bee.’

The rhododendron lace bug has one generation per year. It overwinters as eggs laid on the underside of leaves. Nymphs are about 1/8 inch long and are spiny. Adults are about 1/8 inch long and whitish tan with lacy-looking wings. Damage is usually apparent by early to mid-July. The lace bug sucks on the undersides of leaves and causes stippling on the upper surface of the leaves and tar-like deposits of excrement on the lower surface. Repeated infestations may result in yellowed, sickly plants. Spraying the undersides of the plants to remove the lace bugs was considered impossible because the leaves grow so densely and so close to the ground; thus the affected plants were removed. New planting will take place in 2025.

The related azalea lace bug (Stephanitis pyrioides) has four to five life cycles annually. It infects rhododendrons also but has not been found in the Rhododendron Garden section of the Discovery Garden. Both types of lace bug overwinter.

Lacewing insect © Insect Images: Photographer: Johnny N. Dell

The lace bug is not to be confused with lacewing insects (Chrysoperla species) which are native to the Pacific Northwest and important natural predators providing biological control of aphids.

Treatment for Lace Bug

For non-chemical treatment, Washington State University recommends hand removal of adults and nymphs regularly to limit the amount of visible damage. This can be done with a strong spray of water.

If you choose to use a chemical treatment, two recommended pesticides that are legal in Washington are:

- Safer Brand BioNEEM Multi-Purpose Insecticide and Repellent Concentrate [Organic] Active ingredient: azadirachtin [EPA registration number: 70051-6-42697]

- Safer Brand Garden Defense Multi-Purpose Spray Concentrate [Organic]

Active ingredient: clarified hydrophobic extract of neem oil [EPA registration number: 70051-2-42697]

The best time to treat is May and June. For more information, download the WSU fact sheet on rhododendrons and lace bugs @ (https://hortsense.cahnrs.wsu.edu/fact-sheet/rhododendron-rhododendron-lace-bug/).

The Rhododendron Garden in the Discovery Garden allows the public to view plants as they grow in our specific climate. The damage to some of the small-leaved rhododendrons is sad to see, but it gives gardeners the knowledge to make necessary changes in their gardens to keep them beautiful.

Soon, spring will once again bring forth the eye-catching, luscious blooms on the rhododendron hybrids planted in our gardens and the quietly elegant blooms of our native Western rhododendron at the edges of our woodlands.

REFERENCES AND RESOURCES:

Dale-Crunk, B. (2024) Personal communication.

NASA https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/?intent=121

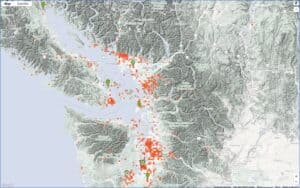

Skagit Climate Science. Air Temperature and Precipitation Retieved at: (http://www.skagitclimatescience.org/skagit-impacts/temperature-and-precipitation-and-ecosystems/#nw-is-warmer).

Washington State University. (2024) Rhododendron: Rhododendron and Lace Bug Retrieved at: (https://hortsense.cahnrs.wsu.edu/fact-sheet/rhododendron-rhododendron-lace-bug/).

Pojar, J. and MacKinnon, A. (1994) Plants of the Pacific Northwest, B.C. Ministry of Forests and Lone Pine Publishing

Nelson, S. (Compiler) (2001) The Pacific Coast Rhododendron Story American Rhododendron Society. Binford & Mort Publishing, Portland, Oregon.

University of Washington: Pruning and Caring for Rhododendrons. https://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/pal/pruning-and-caring-for-rhododendrons/

Washington Native Plant Society (2022) Coast Rhododendron: Washington’s State Flower Retrieved at:https://www.wnps.org/blog/coast-rhododendron-washington-state-flower?highlight=WyJyaG9kb2RlbmRyb24iXQ==

World Meteorological Organization (2025) January 2025 sees record global temperatures despite La Niña Retrieved at: https://wmo.int/media/news/january-2025-sees-record-global-temperatures-despite-la-nina

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sonja Nelson is a Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener, Class of 2009.

Questions about home gardening or becoming a master gardener may be directed to Skagit County WSU Extension Office, 11768 Westar Lane, Suite A, Burlington, WA 98233; by phone: 360-428-4270; or via the website: www.skagit.wsu.edu/mg

Washington State University Extension helps people develop leadership skills and use research-based knowledge to improve economic status and quality of life. Cooperating agencies: Washington State University, US Department of Agriculture, and Skagit County. Extension programs and policies are available to all without discrimination. To request disability accommodations contact us at least ten days in advance.