Hummingbirds in the Garden: Food Sources and Benefits

Food sources for resident Anna’s and migrating Rufous hummingbirds and tips for safely hosting a feeder in your garden.

Subscribe to the Blog >By Joan Stamm, Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener

There’s a wealth of information out there about our beloved hummingbirds-fascinating mythology, a horrifying feather trade history, descriptions of dazzling aerial dynamics, and arduous migratory habits-but this article will focus on beneficial food sources for our resident Anna’s and migrating Rufous, as these hummingbirds are not only an important part of our ecosystem that helps control insects, but are great pollinators. If this weren’t enough, they are simply a delight to watch.

Let’s start with the basics:

In early spring, Anna’s hummingbird finds nectar in the red-flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum) © Photos: Mason Maron | Audubon Society

Insects and Spiders

The least glamorous but one of the most important hummingbird food sources is insects. Female Anna’s, when raising their young, can eat up to 2,000 bugs per day. In fact, Douglas Tallamy, a professor of entomology at the University of Delaware, claims that although “Hummingbirds like and need nectar … 80 percent of their diet is insects and spiders.”

Native trees and shrubs, more than “introduced” varieties, provide the highest potential for attracting native insects. To ensure a steady supply of native invertebrates that all birds, but especially hummingbirds, enjoy, plant a variety of native plants in your garden. Another way to increase insect populations is to leave the leaves in the fall. Many insects hide and winter in leaf litter. Instead of tidying up and throwing all those wonderful leaves in the compost bin, pile them up around your plants and postpone cutting away all the dead flower debris until spring. These practices will increase your insect population, and hummingbirds will help keep your bugs in check.

Make the choice to avoid pesticides.

Pesticides containing neonicotinoid insecticide are widely used by farmers and homeowners, and on pets for flea and tick treatments. Even though neonicotinoids are relatively less toxic to beneficial insects and pollinators, and their use is supported by WSU and USDA, many gardeners prefer to avoid their use. Some research institutions have found that hummingbirds exposed to systemic neonicotinoid insecticides for even a short time can disrupt their high-powered metabolism. Hummingbirds are pollinators. They can visit hundreds of flowers in a day. Any pesticide that can harm bees will likely harm hummingbirds.

Though not native to the Pacific Northwest, the brilliant red flowers of Crocosmia ‘Lucifer’ attracts hummingbirds throughout the summer. © Photo: Nancy Crowell | crowellphotography.com

The Rufous hummingbird is attracted to ‘Black & Blue’ anise sage (Salvia guaranitica) © Photo: Phil Green | philgreen.net

Tree Sap

We don’t often think of tree sap as being an important food source for birds, but when flower nectar is scarce our migrating Rufous hummingbird will turn to sap in tree wells left by red-breasted sapsuckers and woodpeckers. If your garden can accommodate aspen, birch, or pine, you will create another potential food source for our Western Washington hummingbirds; plus providing important nesting and perching habitat.

Native and Non-native Flowers

Along with the protein, fats, and amino acids found in insects and the minerals found in tree sap, other nutrients important to hummingbirds are found in flower nectar. “Scientists have learned that the richness of the nectar matters more than the color of its source,” which in most cases would come from plants native to our region. A perfect example is our native snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus) which has tiny pink (not red) flowers that hummingbirds return to again and again. They also like our native nodding onion (Allium cernuum) with its tiny pinkish mauve flowers. Even osoberry (Oemleria cerasiformis), with its white pendulous flowers, offers good quality nectar early in the season as they are one of the first native trees to bloom.

But if you want to give hummingbirds their preferred red-orange range, try our native red paintbrush (Castilleja miniata), western columbine (Aquilegia formosa), red-flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum), Cascade penstemon (Penstemon surrulatus), and hot pink and scarlet monkeyflower (Mimulus lewesii and cardinelli) to name a few.

Along with natives, and to ensure a steady supply of flower nectar throughout the year, there are many introduced varieties that hummingbirds love. Most notably in my garden are the salvias- ‘hot lips’ and ‘black and blue.’ They also like bee balm, crocosmia, fuchsia, and weigela. For winter bloomers, Ciscoe Morris, the NW gardening guru and host of “Gardening with Ciscoe” recommends witch hazel, Camellia sasanqua ‘Yuletide,’ sweetbox, Daphne odora, Viburnum x bodnantense ‘Dawn,’ Grevillea victoriae, and the Asian hybrid Mahonia x media.

During breeding season, the hummers helicopter from plant to plant until they get their fill, mixing nectar with insect protein to feed their young, which is strictly the female’s job, along with nest building. The males resume their independent lifestyle.

Western columbine (Aquilegia formosa) is native in our area and provides food for Anna’s hummingbird © Photo: Phil Green | philgreen.net

Many enjoy feeding hummingbirds, but doing so comes with the responsibility of keeping the feeders clean and free of bacteria to avoid harming the birds. It may be easier to grow native plants such as snowberry and red currant to help the hummers through late winter. © Photo: Nancy Crowell | crowellphotography.com

Hummingbird Feeders

If you are going to use hummingbird feeders-and it’s really the overwintering Anna’s that mostly benefit as the Rufous is long gone by the end of summer-then the overwhelming advice from experts is that feeders be clean, clean, and clean. Some say feeders should be cleaned every 3 to 4 days, some say 5, and others say if the weather is above 65 degrees, they should be cleaned daily to prevent the sugar water from fermenting. “Sugar water is a nursery for bacteria, mold, and potentially dangerous pathogens.” Fermented sugar water can enlarge a bird’s liver imperiling its health. “Ten percent or more of the hummingbirds who wind up in rehabilitation centers have yeast infections from improperly maintained feeders.” Clean feeders with hot, soapy water or vinegar. Never use bleach as any residue is not only toxic to birds but to the environment in general.

The recipe for the sugar solution is one part plain white non-organic refined sugar to four parts water. Do not use red coloring or any commercial product with chemicals or dye. Boil the solution, let it cool, and fill your feeder. Hang more than one feeder to avoid competition. Hang them away from a window to prevent hummingbirds from flying into the glass and breaking their neck. In summer, hang them in the shade. In winter, hang them in the sun. If temperatures drop, you will need to rig up a heating element to keep the solution from freezing or rotate your feeders throughout the day. If all this sounds like too much work and responsibility-inadvertently harming hummingbirds rather than helping-it might be easier to grow a variety of nectar-rich flowers instead and leave the rest to nature.

Learn from the experts at the

Country Living Expo

& Modern Homesteading

Saturday, January 25, 2025

Stanwood High School

Learn More and Register Here >>

These Gardening Topics and More:

- Fruit Tree Pruning

- Microclimates in the Garden

- Garden Design

- Roses

- Bee Keeping

- Growing Vegetables, Herbs and Flowers

- Tool Care and Maintenance

- Small Fruits: Elderberry and Blueberries

- Growing Lavendar

https://extension.wsu.edu/skagit/countrylivingexpo/

Mahonia x media, pictured here, is an Asian hybrid that blooms in winter. Several native Mahonias also attract hummingbirds and bloom in early spring. © Photo: Nancy Crowell | crowellphotography.com

The coastal hedgenettle (Stachys chamissonis) is a native plant in the Pacific Northwest that thrives in moist soil near forests and provides support to birds, bees and butterflies. © Photo: Nancy Crowell | crowellphotography.com

REFERENCES AND RESOURCES:

BOOKS:

- Link, R.Landscaping for Wildlife in the Pacific Northwest. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. 1999

- Shewey, J.Hummingbird Handbook. Portland: Timber Press. 2021

- Stark, E. M..Real Gardens Grow Natives. Seattle: 2014

- Tallamy, D.Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard. Portland: Timberpress. 2019

ON-LINE:

- All About Birds –https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Annas_Hummingbird/

- Beyond Pesticides: https://beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/2021/02/hummingbirds-are-being-harmed-by-the-same-pesticides-killing-off-bees-butterflies-and-other-pollinators/

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources:https://georgiawildlife.com/out-my-backdoor-beyond-hummingbird-feeder.

- The Humane Gardener: https://www.humanegardener.com/a-fighting-chance/#:~:text=Hummingbirds%20are%20more%20visible%20to,in%20our%20yards%20as%20well.%E2%80%9D

Joan D. Stamm

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Joan D. Stamm, is a certified Skagit County WSU Extension Master Gardener and the author of several books, including The Language of Flowers in the Time of COVID: Finding Solace in Zen, Nature and Ikebana.

The Western Washington Fruit Research Foundation, now called NW Fruit, was created in 1991 to help support the tree fruit research at the Washington State University (WSU) Northwestern Washington Research & Extension Center (NWREC) Fruit Horticulture Program in Mount Vernon. It is dedicated to supporting research and educating the public about the special fruit-growing conditions of the Pacific Northwest region.

The Western Washington Fruit Research Foundation, now called NW Fruit, was created in 1991 to help support the tree fruit research at the Washington State University (WSU) Northwestern Washington Research & Extension Center (NWREC) Fruit Horticulture Program in Mount Vernon. It is dedicated to supporting research and educating the public about the special fruit-growing conditions of the Pacific Northwest region.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

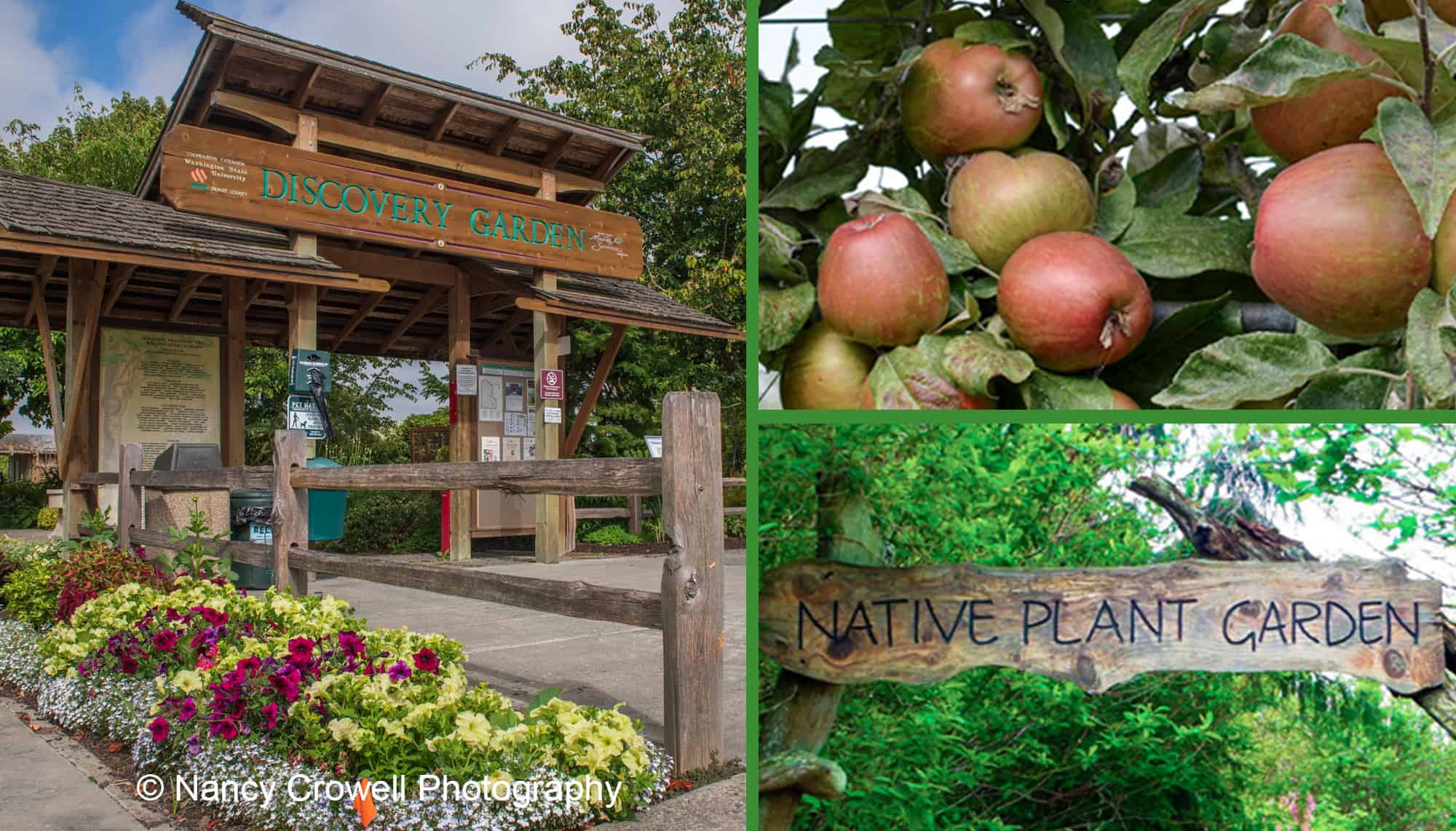

While all three of these gardens are open to the public daily, the Annual Open House is focused on educating and inspiring visitors interested in many specific areas of interest, including pollination, water-wise gardening, native plants and raising fruits and vegetables in the Skagit area.

While all three of these gardens are open to the public daily, the Annual Open House is focused on educating and inspiring visitors interested in many specific areas of interest, including pollination, water-wise gardening, native plants and raising fruits and vegetables in the Skagit area.

Janine Wentworth became a master gardener in 2018. She and Kay Torrance are co-chairs of the Discovery Garden Open House.

Janine Wentworth became a master gardener in 2018. She and Kay Torrance are co-chairs of the Discovery Garden Open House.